To put in context the surprise that greeted the two-day Boxing Day Test just gone, consider the rarity by arithmetic. The match in Melbourne was Test number 2,615, and was two-day Test number 27. You don’t need a calculator to see that’s roughly 1%. And yet we’ve had two such matches in the current Ashes series, plus another in Australia three years earlier. We’ve had half a dozen two-day Tests worldwide since 2021. What gives?

Nine two-day Tests – fully one-third of the total – happened in the 1800s, when pitches could become swamps or shooting galleries. The next few mostly involved weak teams in their early years of development. Australia and England each dished one out to South Africa in the tri-series of 1912, and the South African team was little stronger when ripped up by Clarrie Grimmett and Bill O’Reilly in 1936. Australia also bashed up a new West Indies team in 1932 and New Zealand in 1946.

But that was it, from just after the second world war until the new millennium, with not a single two-day match. In 2000, England demolished a ghostlike West Indies at Leeds to signal the start of the Caribbean’s terminal cricket demise, and Australia’s golden era team took apart Pakistan in Sharjah in 2002. Then we were back to weak emerging teams, with five two-dayers involving Zimbabwe, Afghanistan, or both.

The other few were in extreme conditions: India thumping England in Ahmedabad with a pink ball that plunged through the soil from the first over, South Africa greeted with a disastrously underprepared fast pitch at Brisbane, then offering India something similar in Cape Town. The recent two Ashes pitches were in fact the best of the lot.

So of the 27 matches in question, eight have been between England and Australia: two in this current series, the other six more than a century ago. These are the two-day Tests between the old rivals that came before.

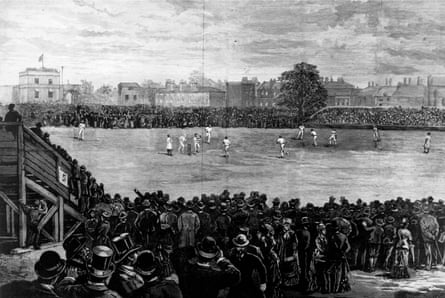

1882: Ashes inspiration

The best of them all – this one isn’t technically an Ashes contest, because it’s the match that inspired the Ashes. Like in Melbourne last week, 20 wickets fell on the first day at The Oval, but given the short bowling approaches of the time, the day spanned 151.3 overs. England were well on top in a low-scoring era, with 101 to follow Australia’s 63. There was, as the match report makes clear by beginning with a display of every English player’s superior batting average, no doubt that the England team was supposed to be better at home.

The next morning, though, the Australians built into a lead. The score was 99 for 6 when superstar Billy Murdoch was joined by Sammy Jones, and the pair soon added another 15 runs. Worried that their lead would climb into triple figures, the ever sharp WG Grace stole in to break the stumps while Jones was patting down a spot on the pitch, and appealed for run out. It was given, Australia got bowled out for eight more runs, and the lead was held to 85.

The problem was, Frederick Spofforth was next in to bat, and the man known as The Demon was incensed by what he said was Grace’s cheating. He tore strips off the Englishman in the dressing room at the innings break and vowed to make them pay. The vow was upheld in a way to please the numerologists: seven Demon wickets in the second innings to match his seven in the first, England were all out 77 to lose by seven runs. A cremation notice for English cricket was placed in a newspaper, and the Ashes began.

1888: soggy summer

If a two-day match is notable, what about an entire series of themin Tests at Lord’s, The Oval, Old Trafford? Several factors conspired. Of all Test bowlers with at least 50 wickets, the list of best averages starts with George Lohmann, JJ Ferris, and Billy Barnes, then skips two places to Charlie Turner, Bobby Peel, and Johnny Briggs. All of them played throughout this series, spread across the teams. That is, six of the eight most successful bowlers of substance in history played at the same time.

Their figures were helped by a wet summer with rain ruining the pitches for the first and third Tests. Only three team innings out of 10 got past 100. On the one good pitch, Australia collapsed anyway by lunch on day one. The visitors won the first shootout but got done by an innings in the next two encounters.

At least they made the most of their tour with another 34 first-class fixtures between May and September. Indeed, by the time Australia lost the second Test to square up the series, it was the middle of August and they had played 25 competitive matches. If anything, they overprepared.

1890: rain-ruined pitch

With Lohmann, Ferris, Turner and Barnes still around, it was another sad season for day-three ticket holders at The Oval. Again the ground was drenched with rain before the match, and again the bowlers cut loose on the drying mud, with 22 wickets on the first day. Australia scratched together 98, England 100, then Australia 102.

That left 95 for England, and they moved comfortably to within a dozen runs of that target four wickets down, only for a tumble to begin. With Turner and Ferris in tandem, four wickets fell for 10 runs, and memories of the Spofforth effort eight years earlier bubbled away. After a string of maiden overs, with tension abounding, an errant throw from Jack Barrett allowed England to pinch the win, two wickets in hand.

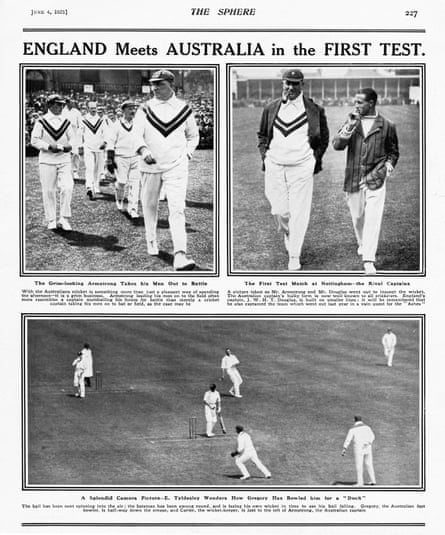

1921: bold new tactics

In what was until recently the only two-day Ashes Test beyond the morass of the 1800s, this one at Trent Bridge does have the context of an English game still battered by the first world war. It is also the site of a turning point: the proof of concept for the fast-bowling opening pair.

Jack Gregory and Ted McDonald had first opened the bowling together in Australia six months earlier. They had been effective across three Tests on flatter pitches without dominating. But captain Warwick Armstrong liked the concept and wanted more. When he rolled it out for the first Test of the series in England, it was devastating.

Gregory did the damage in the first innings, three wickets off the top and six by the close, but there was no respite at the other end. Most teams in those days used at least one slow bowler with the new ball, so this was something unfamiliar. Armstrong himself sent down only three overs of leg spin; Gregory and McDonald bowled the rest, taking nine wickets between them. When they went again the next day they added seven more, and it was McDonald’s turn for a five-wicket haul. The match was done, and the game was changed.

.png)

1 month ago

24

1 month ago

24