Laura KuenssbergSunday with Laura Kuenssberg

BBC

BBC

"Keir can't be the last gasp of the dying world order," warns a minister.

The prime minister finds himself in charge when the globe is being bent into a new shape by his big pal in the White House.

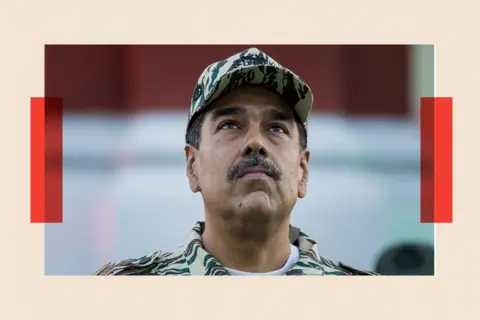

While a lot has gone wrong at home, Downing Street's handling of events abroad has broadly been considered a success. But as the pace of Donald Trump's activity around the world picks up - particularly in Venezuela and Greenland - the prime minister's increasingly assertive opponents at home are set on turning one of his few sweet spots sour.

It is true there has been some squeamishness, particularly on the left of the Labour Party, over Starmer's closeness to Trump. It is a symptom of a traditional distaste for the schmaltz of the "special relationship", that did not start and will not end with Starmer and Trump. Think Blair being accused of being Bush's poodle over Iraq, or parodies of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan taking a spin on the White House dance floor.

Whatever the personal vibes, it is always a transaction: "The unavoidable cost of doing business," one Labour MP says. This time, if you show loyalty and friendship to a controversial leader, it will be easier to agree a better trade deal than most of the rest of the world. Dangle royal invites to the US president, or be understanding of big US tech firms' desires, and there is a friendlier reception to requests for support for Ukraine.

So far, so successful, with senior figures in government believing their foreign policy guru, Blair-era adviser Jonathan Powell, is "playing a blinder". But according to one senior Labour MP, there is a growing risk of "being linked to the madness". The prime minister could find himself squeezed by accusations of weakness from both sides of the aisle and with one big policy problem rising up the rails: how much money to spend on defence.

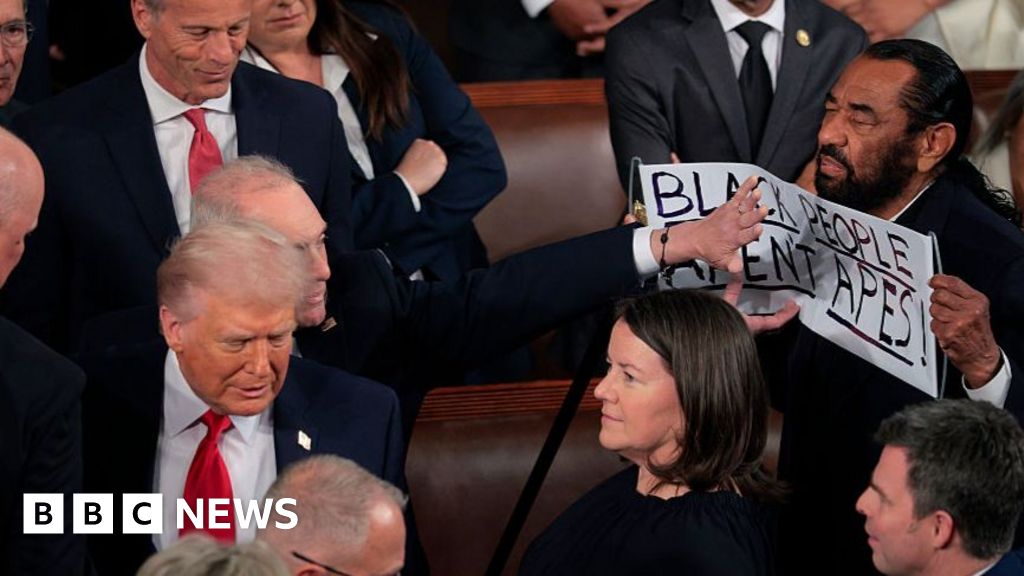

Traditionally, the official opposition in the UK tends to stick with the government on foreign policy - I wonder if that feels rather quaint in the turmoil of 2026. An increasingly confident Kemi Badenoch, who will join us on the programme on Sunday, is paying scant attention to that now.

She chose, unusually, to try and blast the prime minister on foreign policy in the Commons this week - claiming Starmer was irrelevant because he had spoken only to Trump's senior advisers five days after the strike on Venezuela, not to the president himself. She also lambasted him for not giving MPs and the public the full details of the deal agreed with France and Ukraine to put UK troops on the ground in the event of a peace agreement.

Her team reckons she managed to puncture his authority on foreign policy this week. And you can expect the Conservatives to keep building an argument that the UK is not showing enough strength abroad. That begs the obvious question: what exactly would Badenoch do differently?

PA

PA

It is far from inevitable she would somehow be involved in the inner Trump decision-making team in a way that Starmer is not. Would she have been able to broker a deal that could help guarantee potential peace in Ukraine, or would she mount more operations against Russia's shadow fleet, like the UK-supported seizure of the Marinera tanker in the North Atlantic this week? In truth, the job of the opposition is to make arguments, not take action.

Those arguments are coming thick and fast on foreign policy from the left too, both outside and inside Labour itself. The Lib Dems, who are within a whisker of Labour in some polls, also took the unusual step of using both their questions at PMQs this week to ask about foreign affairs. Lib Dem leader Ed Davey's team noted his comments about Venezuela were watched on Instagram more than anything else he had ever posted, with nearly 10 million views - not the be all and end all, but it is interesting that it cut through in this noisy world.

With the frenzied pace of Trump's foreign activity picking up, a senior Lib Dem source says: "We see the opportunity - Starmer is so closely hitched to Trump there's a growing risk it's damaging - and it works on the doors: lots of Labour voters are anti-Trump but pro-Nato."

Sources point to the party's significant breakthrough when they opposed Tony Blair over Iraq. The parallel is not pure, but Labour's discomfort is plain, and their rivals are keen to pounce.

The surging Green Party are all too happy to scoop up unhappiness about Trump to Starmer's detriment, too. A senior party source says: "It's hugely problematic for the prime minister. He's put so many of our eggs in the Donald Trump basket. Lavishing him with a second state visit - to stroke his ego - was always going to end in tears."

Inside Labour, there are pockets of unhappiness on the party's traditional left, with some MPs openly questioning the government's lack of condemnation of Trump's action against Venezuela, and there is unease for some after the UK backed the seizure of the Marinera, too.

Even some supportive colleagues who praise the prime minister's actions on the world stage worry about how he handles the perceptions now at home. "The responses have been the response of a diplomat's brain, not a political one," says one, "and if you don't take a strong political position too, you'll be attacked by both sides."

That said, such visible international turmoil may make the prospect of a challenge to Starmer less likely. Any leadership contender flirting with the idea of a challenge could look self-indulgent when the international situation is in such flux.

Shutterstock

Shutterstock

While Trump's international rollercoaster gives new opportunities to Starmer's opponents, grave international moments make stability in his own party a greater prize. And foreign policy is not generally considered the strong suit of Labour's main current foe, Reform UK. It is easier for Labour to beat off their criticisms on foreign policy than attacks on immigration.

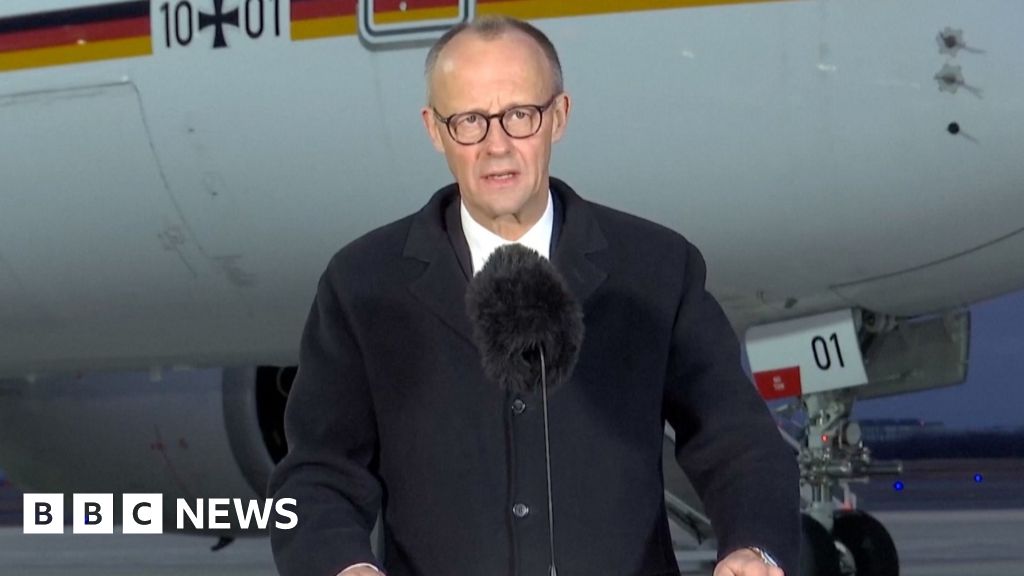

Forget party political attacks for a second, the dramatic start to the year around the world has put a fresh focus on a conversation we have had regularly in recent months: how much more taxpayers' cash is going to have to go to defence as the world is less stable, and has the government really made the decisions to make it happen? One insider told me: "Defence spending is a proper wound now - it's not just the chiefs grumbling."

How much of your cash to spend on protecting the country and by when was already a tricky issue. The prime minister is fond of saying we are in turbulent times - as he argued in our long interview last week. He believes the UK and the rest of Europe must put much more money aside to protect itself.

On Friday, the defence secretary, John Healey, in response to reports of chunky shortfalls in the money available, reiterated that what is happening around the world demands a new era for defence. Ministers have already promised to increase defence spending at a rate faster than since the end of the Cold War - though it comes with a big "but".

Reuters

Reuters

Before the turn of 2026, the former chief of the defence staff, Sir Tony Radakin, argued publicly that there may not be enough money to protect budgets from cuts. The defence secretary told us that was wrong. But the following week, the new chief of the defence staff told us yes, there had already been some cuts to some capabilities. Awkward!

And that spat, and the government's big defence review, was before the United States' new security strategy, which, in dramatic language, laid bare the approach of the Trump White House. It was before the American strikes on Venezuela, which showed he would act, not just threaten. And it preceded the White House's re-stated ambition this week to possess Greenland, even using military force - yes, it may go after a member of the defence alliance the US itself is signed up to defend.

After Trump's recent actions, the question of how much the UK is really willing to pay for its own protection, and what politicians are willing to sacrifice to make that happen, becomes more urgent by the day.

Many argue, including some opposition parties, that ministers have already vowed to spend more on defence. But have ministers really accepted how big that shift needs to be, or levelled with the public about it? That's a different question.

A rule of British politics has long been that voters do not switch on foreign policy: what happens at home is more important. As one government source said: "People want to see us handle the foreign stuff competently but it's not really what people care about - they only vote on foreign affairs grounds in genuinely exceptional circumstances."

But the opposition parties are eager to open up a new front to attack the prime minister. There is a genuine and profound question over the government's priorities in a dangerous world.

All politics is local, so the saying goes. But after the last seven days, could 2026 be the exception that proves the rule?

Top image credit: Getty Images

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. You can now sign up for notifications that will alert you whenever an InDepth story is published - click here to find out how.

.png)

1 month ago

22

1 month ago

22