Sima KotechaSenior UK correspondent

BBC

BBC

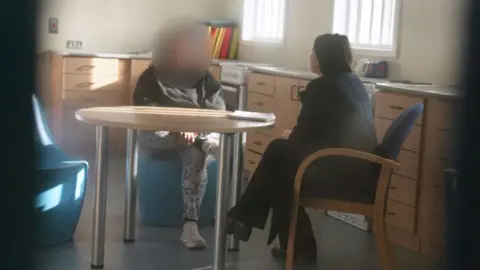

The BBC visited HMP Send and spoke to women including Tina

Tina was 16 years old when she says she was forced to get married.

She describes what followed as decades of "relentless" abuse, including being "punched in the face a few times...[and] an incident where my head was smashed into a wall".

It culminated in divorce - after which her family cut her off - and a downward spiral into drug and alcohol abuse and depression.

Now in her 40s, Tina - not her real name - is serving a six-year sentence for importing class A drugs.

"I did make bad choices and I regret the choices I made," she says, "but in all honesty I feel like I'm grateful that I got arrested when I did."

Tina is one of 243 women jailed at HMP Send - a women's prison nestled in rural Surrey.

Most of the women here are doing time for non-violent offences, and staff say it is likely the majority have experienced domestic violence at some point in their lives.

Tina says staff at HMP Send have helped her "become a better version" of herself.

But she believes a lot of what she has done in prison could have taken place in the community.

"I just feel like maybe my punishment was more than it needed to be," she says.

The government says it wants to send fewer non-violent offenders on short sentences to prison.

Women would appear a prime focus for this, with almost three-quarters of those incarcerated in 2020 being held for non-violent offences, many of whom are vulnerable.

Speaking to the BBC, Prisons Minister Lord Timpson said there were too many women who were victims of domestic abuse in the system.

These women, however, are criminals and some will have little sympathy for their circumstances - they have broken the law.

Six cell blocks

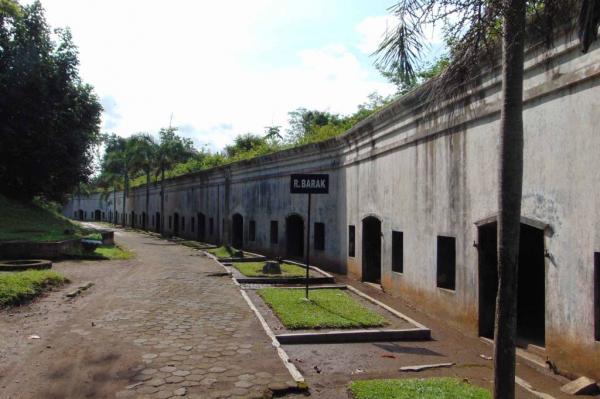

I've visited numerous men's prisons for the BBC, but this is the first I've been in one that accommodates women. The differences are stark.

The long driveway to HMP Send - about six miles from Woking - leads to an intimidating entrance. Coils of barbed wire top the cream-coloured high metal fencing.

But once we walk through the main gate, the atmosphere changes rapidly. It looks more like a college campus with the occasional patch of grass punctuating the cell blocks.

It's smaller than the prisons I've previously visited - the Victorian men's prisons house hundreds more inmates.

The lines of cells are longer, with offenders able to see onto other cells from landings up high. The volume here is lower too. There is less shouting, banging and clanging and fewer voices raised in anger.

The women are jailed in six cell blocks. Their crimes vary in severity, from murder and fraud to theft and prostitution.

Twenty-five-year-old Behnaz is serving a five-year sentence for possession of a firearm. Her meticulous hair and make-up is not what you might expect from an inmate.

Behnaz says inmates leave prison with more more issues than they had coming in

"I don't believe prison is the place to get rehabilitated," she says. "You leave prison with more issues than you had coming in, the trauma of actually being in this environment and the things that you see and the things that you hear."

But, she adds: "There are parts of my crime that I 100% took accountability for, so being in prison is something that I've made peace with and I'm OK with."

There are 3,477 women in prison across England and Wales - just 4% of the total prison population.

Some 72% were serving sentences for non-violent offences in 2020, according to the Prison Reform Trust.

According to the Ministry of Justice, female offenders are often vulnerable, with more than half of women in prison reporting being victims of domestic abuse.

Tanya Marsden, the residential supervising officer at HMP Send, says: "When it comes to male staff, that can be such a massive trigger for some of the women... trying to build that trust with some of these prisoners is quite difficult at times. But what we're excellent at is we just show them that we're here [for them]."

HMP Send is one of only a few prisons in England that has a dedicated programme for those suffering with brain injuries from domestic abuse.

The charity Brainkind works with women here - offering rehabilitative sessions and teaching skills - to help them deal with their condition which may have been caused by non-fatal strangulation or other forms of physical violence.

Research suggests that a prisoner's offence can be partially attributed to acquired brain injuries, which are found to impair judgement and skew decision making.

Lord Timpson tells the BBC he's met "far too many women" in prison who are victims of domestic abuse - describing them as "black and blue".

"I don't believe prison is the right place for them. They need to be in a safe place, preferably with their kids and away from violence."

He says a prison place will always be needed for a violent offender, but policymakers need to "follow the evidence".

He adds: "And the evidence says that a lot of women go to prison for short sentences, their kids go into care, and when they leave prison they commit further crimes. What we've got to do is to reduce the amount of reoffending."

HMP Send looks more like a college campus than a jail

New laws expected to come in next year will mean a reduction in short custodial sentences and more community-based punishment.

With 16% of women serving 12 months or less for their crimes as of the middle of 2024, the legislation is likely to significantly reduce the number of women jailed.

Shadow justice secretary Robert Jenrick said more than half of crime was committed by 9% of criminals and said the government needed to make sure these "hyper-prolific offenders" stay behind bars - regardless of their sex.

"However, there are occasions where public protection should be balanced," he said. "For pregnant women, those with young children, or those who are themselves the victims of domestic abuse, alternative forms of punishment will often be far more appropriate."

It costs the taxpayer more than £52,000 per prisoner every year, so supporters of the government's position say there's a clear money-saving win through not jailing them in the first place.

However, non-custodial sentences are not necessarily a cure-all. Critics of the government say a lack of support services and rehabilitation programmes could lead to reoffending.

Several probation officers have privately conveyed concern over whether they'll be able to provide the support women with complex needs will require in the community - with their workload already said to be at maximum levels.

And some inmates argue about the deterrent effect. One asked: "If women know they won't be jailed will they be more likely to commit crime or coerced into it?"

It's clear the government needs to navigate these issues thoroughly to avoid the revolving door of offending, conviction and jail.

The charity Women in Prison indicates that 56% of women serving a custodial sentence will reoffend within a year.

Alida is serving a prison sentence for serious fraud offences, and believes it is the right place for her to be in.

She says while some women in the prison hold their hands up and take responsibility for their offence, others "blame somebody else for it".

"There's no smoke without fire, you know, and I don't think the system gets it that wrong at the end of the day," she says.

.png)

13 hours ago

7

13 hours ago

7