Nick TriggleHealth correspondent

BBC

BBC

"Fat people just need more self-control." "It's about personal responsibility." "It's simple, just eat less."

These were some of the 1,946 comments, posted by readers, beneath an article I wrote last year about weight-loss injections.

The idea that obesity is simply a matter of willpower is held by a great many people - including some medical professionals.

Eight out of 10 people said obesity could be entirely prevented by lifestyle choices alone, according to a study of people in the UK, Australia, New Zealand and the US, which was published in medical journal The Lancet.

But Bini Suresh, a dietitian, who has spent 20 years working with obese and overweight patients, is exasperated by the idea.

This, she believes, is only a fraction of the picture.

"I frequently see patients who are highly motivated, knowledgeable and trying consistently yet still struggling with weight."

"Terms like 'willpower' and 'self-control' are the wrong words," agrees Dr Kim Boyd, medical director at WeightWatchers. "For decades people have been told to eat less and move more and they will lose weight... [But] obesity is much more complex."

She and other experts I spoke to suggest there are myriad reasons a person might be obese, some of which are not yet fully understood: but what is clear is that it is not a level playing field.

Getty Images

Getty Images

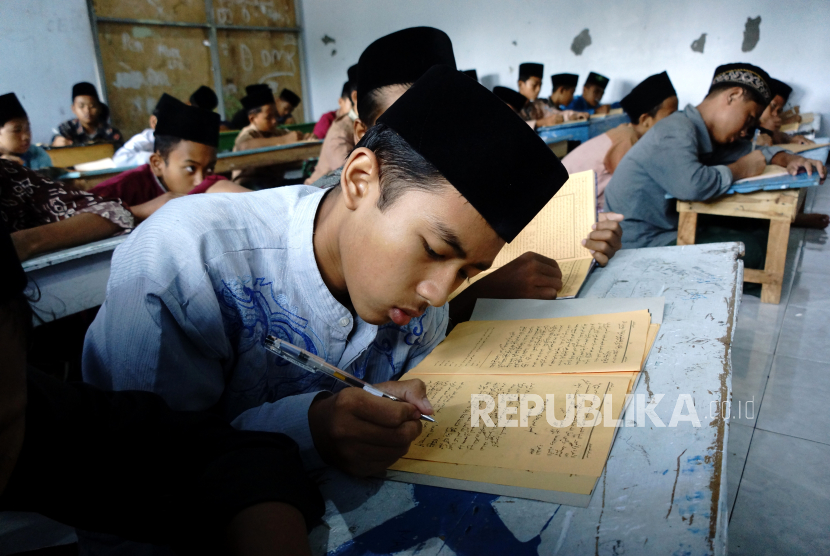

Expecting weight management and maintenance to rely purely on willpower is both unrealistic and unfair, argues Bini Suresh, who is head of dietetics at the Cleveland Clinic in London

The government has turned to regulation to try to tackle this.

Its most recent move – banning junk food advertising on television before 9pm and completely for on online promotions – comes into effect today.

Yet many think this too will only go so far in tackling what is now an overwhelming obesity problem in the UK - one that affects more than one in four adults.

A battle against biology

"The amount of weight people gain is significantly influenced by their genes and those genes are relevant for everybody," explains Prof Sadaf Farooqi, a consultant endocrinologist who treats patients with severe obesity and related endocrine disorders.

She says that certain genes affect the brain pathways that regulate hunger and fullness in response to signals sent by the stomach to the brain.

"Variants or changes in these genes are found in people with obesity, which means they feel more hungry and are less likely to feel full after eating."

In Pictures via Getty Images

In Pictures via Getty Images

Obesity can lead to heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes and some cancers

Perhaps the single most important of these genes – at least the most important of those known about so far – is the MC4R gene. A mutation in this gene, which encourages overeating and means we feel less full, is carried by roughly a fifth of the global population.

"Other genes affect metabolism – how quickly we burn energy," adds Prof Farooqi.

"That means some will gain more weight and store fat from eating the same amount of food, than other people do, or they will burn less calories when they exercise."

She estimates that there are likely to be thousands of genes that have an influence on weight and that we only know in detail about roughly 30 to 40 of them.

The science behind yo-yo dieting

Yet even this is only part of the story.

Andrew Jenkinson, a bariatric surgeon and author of Why We Eat Too Much, explains that everyone has a weight their brain understands or thinks is the right weight for them - regardless of whether it's a healthy weight or not.

It's known as set weight point theory.

"This [set weight] is determined by genetics, but also by other factors, such as your food environment, stress environment and sleep environment."

And it means that body weight is like a thermostat: your body aims to maintain that preferred range. If weight drops below this "set point", hunger rises and metabolism slows, just as a thermostat turns up the heat when it's too cold, according to that theory.

Once your point is set, it's very difficult to alter it by willpower, Dr Jenkinson argues.

This can also explain yo-yo dieting. "For instance, if you're 20 stone and your brain wants you to be 20 stone and you go on a low calorie diet and lose two stone, your body's reaction to that is just the same as if you were starving," he says.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Some will gain more weight and store fat from eating the same amount of food, than other people do, says Prof Farooqi who leads the Genetics of Obesity Study, based at the University of Cambridge. She estimates that there are likely to be thousands of genes that have an influence on weight

"It's going to have that reaction of voracious appetite, food-seeking behaviour and a low metabolism," he adds. "These appetite signals are profoundly strong. They're as strong as a thirst signal, they're there to help us survive…

"A voracious appetite is something that's really, really difficult to ignore."

As to the science behind this, Dr Jenkinson points to the role of leptin, a hormone produced by fat cells. "It acts as a signal to the hypothalamus, the part of the brain that basically controls your weight set point, to tell [it] how much energy storage the body has.

"The hypothalamus will look at the leptin level and if it looks like we're storing too much energy or too much fat, it will automatically alter our behaviour by decreasing our appetite and increasing our metabolism."

At least that's how leptin should work. Often, it fails, particularly in the Western food environment, he explains.

Getty Images

Getty Images

A report last year by The Food Foundation also suggested that healthier foods are more than twice as expensive per calorie than less healthy foods

This is because the leptin signal shares a signalling pathway with insulin. "So if insulin levels are too high, it actually then dilutes the leptin signal and suddenly the brain can't sense how much fat is stored."

The good news is that this set point isn't fixed – it can shift gradually through sustained lifestyle changes, improved sleep, stress reduction and long-term healthy habits.

Much like resetting a thermostat – over time, slow, consistent adjustments can help the body accept a new, healthier range.

Obesity in UK: The perfect storm

None of this accounts for the rise in obesity – after all, our genes and the biological makeup of our bodies have not changed.

The proportion of adults classified as overweight or obese has steadily risen over the past decade, with the Health Foundation's 2025 analysis indicating that more than 60% of UK adults now fall into this category (including around 28% who are obese).

Part of this is down to the sheer volume – and affordability – of poor quality, high-calorie foods, and in particular ultra-processed foods. Add to that aggressive marketing and advertising of fast food and sugary drinks, growing portion sizes, and limited opportunities for physical activity (often due to urban design or time pressures), and it makes for a perfect storm.

Getty Images

Getty Images

The government has introduced a ban on advertising certain unhealthy foods on television before 9pm and a complete ban on online promotions - it comes into effect today

"[As a result] we have become more obese as a population and, of course, those with a greater genetic propensity to put on weight have done so," says Prof Farooqi.

Public health experts refer to this as the obesogenic environment, a term first used in the 1990s as researchers began linking rising obesity rates to external factors like food availability, marketing, and urban design.

Together, many experts argue, these factors create constant cues and pressures toward overeating and inactivity, meaning even highly motivated individuals struggle to maintain a healthy weight.

But all of this also explains why willpower has become more of a loaded term too.

The personal responsibility debate

Sitting in her office at Newcastle City Council, public health director Alice Wiseman can see food everywhere. "There are coffee shops, bakeries and takeaways. You can't go to school or work without passing a food place.

"Visibility matters – if you pass lots of takeaways on your way to work, you're more likely to buy one. Your body's almost reacting to the food around it."

In Gateshead, where she is also public health director, planning permission has not been granted to a new hot food takeaway since 2015.

But across the wider country, the fast-food and takeaway industry has continued to grow – it is worth more than £23bn a year.

And UK food advertising spend is dominated by products high in fat, salt and sugar, such as confectionery, sugary drinks, fast food, and snacks, according to the latest Ofcom Communications Market Report.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Some argue regulation is important in tackling obesity

But Ms Wiseman suggests the new measures introduced today to restrict TV and online advertising of junk food – or officially "less healthy food" – will only go so far.

A report last year by The Food Foundation also suggested that healthier foods are more than twice as expensive per calorie than less healthy foods.

"In families where money is tight it is difficult to afford to eat healthily," says Ms Wiseman.

"I'm not saying personal responsibility doesn't have a role to play. But when you think about it, you have to ask what has changed? We haven't suddenly got less willpower."

Ms Suresh agrees. "We're living in an environment engineered for over-consumption."

"Obesity is not a failure of character. It's a complex, chronic condition shaped by biology and a highly obesogenic environment. Willpower alone is not enough and framing weight loss as solely a matter of discipline does harm."

However, others have a different take on the word "willpower".

Prof Keith Frayn, author of A Calorie is a Calorie, agrees many overweight people would probably not have been so, 40 years ago. "It is the environment that has changed, not their willpower or anything else," he says.

But he adds: "I worry that dismissing 'willpower' makes it too easy to resign oneself to being at a weight that may not be what is desired, or best for health."

He points to large databases of people who have successfully lost weight and have maintained that weight loss, for example the National Weight Control Registry in the USA, with over 10,000 participants.

"Those people describe both losing weight and keeping it off as 'hard', the latter even harder than the former…

"I would suggest that if you were to tell those people that willpower has nothing to do with it, they would be quite affronted."

'You can't legislate people into shape'

The broader debate, of course, is how much responsibility the state should hold.

Ms Wiseman believes regulation is an important tool in tackling obesity, arguing that promotions such as buy-one-get-one free deals encourage impulse buying. But Gareth Lyon, head of health and social care at right-leaning think tank Policy Exchange, argues that more legislation is not the way forward.

"You can't legislate people into shape," he says.

"Bans and taxes on the foods that people enjoy eating are effective only in making life harder, less enjoyable and more expensive for people at a time when Britain is already struggling with the cost of living."

Christopher Snowdon, head of lifestyle economics at the Institute of Economic Affairs, a right-leaning think tank, also believes that obesity is an "individual problem", not a public health one.

'[Obesity] is because of choices made by that individual," he argues. "So ultimately, you can't go much beyond the individual. I find it a fairly bizarre idea that it's the government's responsibility to make people slimmer.

"I'd like to see a serious independent evaluation of these policies and if they don't work they should be repealed."

Getty Images

Getty Images

The fast-food and takeaway industry has continued to grow across the country - it is worth more than £23bn a year.

As for willpower, this will always play some sort of a role – what varies is the extent to which experts think it does.

Ms Suresh believes it is only one part of a bigger tapestry. And the first step is about educating people about what other factors are at play.

"This perspective shifts the focus from a moral judgement about willpower to a compassionate, science-informed support system which ultimately offers better chances for long-term success."

There are also ways to strengthen willpower, argues Dr Eleanor Bryant, a psychologist at Bradford University. "It's not constant all the time. It's affected by your mood, how tired you are and, in terms of eating, how hungry you are…"

What also matters is how you think about it. There are two types of willpower – flexible and rigid. Someone who is rigid sees it as black and white. "If you succumb to temptation you basically give in. You eat that biscuit and then you carry on eating."

In psychological terms, this is known as disinhibited eating. "Whereas, someone who is flexible says, 'OK, I've eaten one biscuit… but I will stop there,'" says Dr Bryant. "Needless to say, being flexible is much more successful."

But she says: "Exercising willpower with food is probably more difficult than in other areas [of life]."

Ms Suresh agrees, though she says that once people understand the limits of willpower, their ability to exercise it actually strengthens.

"When these patients understand that their struggle is rooted in biology, not lack of discipline, and are supported with structured nutrition, consistent meal patterns, psychological strategies and realistic goals, their relationship with food improves markedly."

Top picture credit: Getty Images

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. You can now sign up for notifications that will alert you whenever an InDepth story is published - click here to find out how.

.png)

1 month ago

26

1 month ago

26