“I feel like a medieval pilgrim being ushered into a chapel to behold some holy relics,” whispers Tom Holland as we head deeper into the bowels of the Melbourne Cricket Ground. The historian and The Rest Is History Podcast co-host, his wife, Sadie, and producer Dom are getting an exclusive look at some of the items that make up the new Shane Warne “Treasures of a Legend” exhibition soon to be unveiled at the Australian Sports Museum inside the famous ground. I’m lucky enough to be tagging along.

Jed Smith, the genial manager of the museum, is giving us Pom pioneers the sneak peek. Money can’t buy this access, but a global juggernaut of a podcast seemingly can. The night before Holland and his podcast partner, Dominic Sandbrook, had “played” the Sydney Opera House. They are fresh off the plane to Melbourne with a gig at the Palais Theatre in St Kilda later that evening, a few hundred yards from the very cricket ground where Warne first bamboozled with those fizzing leg-breaks.

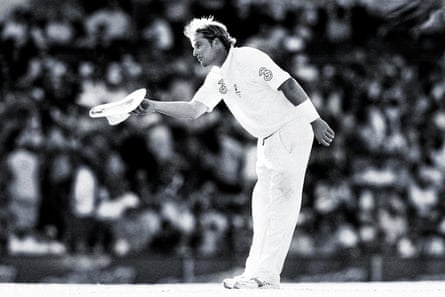

Holland is a huge cricket fan and bowls devastating medium pace for the Authors CC. His six-hitting and hat-trick-taking have become stuff of myth and legend, with perhaps more emphasis on the former. “Will we get to see the ball of the century?” Holland asks as we excitedly shuffle towards an unmarked green door. Smith pushes the door and holds it open for us to file through. “Oh yes,” he replies with a smile the width of one of Warne’s lurching leggies.

We enter a vast room of metal shelving units and huge tables. There are boxes and bags. There are hats, helmets, bats and stumps, boots and balls. So many balls. “There’s a real poignancy to it,” says Smith. “He was actually curating all this stuff as he went. He was a maverick, in the very truest sense of the word, but he was methodical too.”

It transpires that Warne would return home after a series and empty his kitbag out, together with Simone, his then wife and mother of his three children. The couple would date, inscribe and catalogue the balls, stumps and other items that he had collected. Year upon year Warne’s achievements and legend grew. More items were chalked up and kept for safekeeping.

“It’s almost as if he knew that someday people would want to come and see all this stuff, the objects, now artefacts that underpinned his career and life,” says Smith.

There’s his famous white floppy sun hat, the one doffed in the indelible image as he took his final Test bow in 2007. There is the stump from his Trent Bridge balcony boogie in 1997. There is the helmet he donned with a sheepish grin during a 1999 ODI against England as he emerged from the MCG changing rooms in his flip-flops and joggers to quieten a mob throwing golf balls and beer bottles from the notoriously hostile Bay 13 section. Seconds later that same mob were bowing down to Warne en masse. The stand now bears his name.

The MCG is the fitting place for the items, a son of Melbourne and proud Victorian. Warne’s family got in touch with the museum and are a key part of the exhibition. “The MCG is the place we all wanted them to end up,” says Smith. “Shane’s children were desperately keen to be involved. They have provided voiceovers that serve as a guide to the exhibition. It gives it real emotion.”

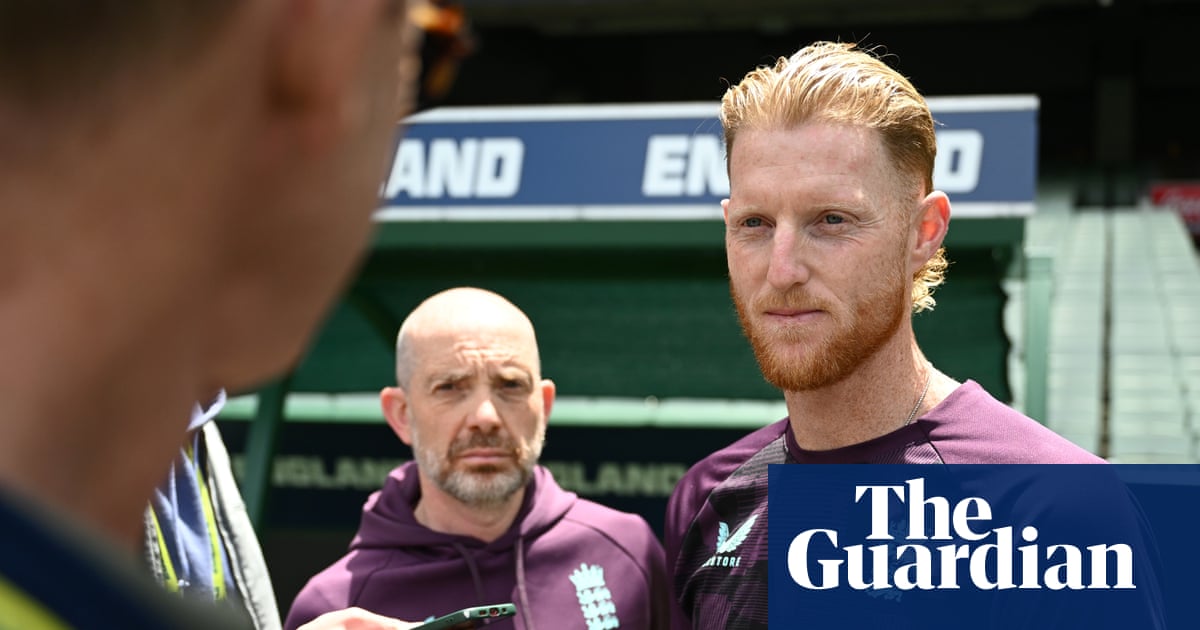

Smith guides our slack-jawed group around the room. It says something about Warne’s unique appeal that four English people are rendered childlike and agog upon seeing the totems of the great Australian’s career, especially when you consider Ben Stokes’ men are getting pulverised in the Ashes. Warne always transcended.

The items reveal little glimpses into the man. Never buying into the cult of the baggy green, Warne wrote that that the reverence some of his teammates gave the cap made him want to “puke”. It turns out he had four. “Inside one of them it says ‘on loan from Cricket Australia’,” chuckles Smith.

There’s umpteen pairs of bowling boots, all with a hole cut out of the big toe area. The pair Warne had on when he took his 249th Test wicket, the one that saw him go past Richie Benaud as Australia’s premier leg-spinner are sat just apart on a shelf. “Beneaud. 249” is scrawled on them in marker pen. Spelling mistake, bowler’s own.

We come to the balls. A reverent hush descends. “To have this … it’s just magical,” says Smith as he hands Holland the ball that changed Warne’s life and gave cricket one of its iconic moments. “Am I allowed to hold it?” Holland asks in disbelief. He cradles it like a newly hatched fledgling. Once-in-a-lifetime photos are hurriedly posed for and taken. The ball comes to me and the cellophane is peeping open. The seam that Warne imbibed with his wizardry is winking up at me. The rest are momentarily distracted. I shouldn’t. I mustn’t. But of course, I do.

Like Harvey Keitel in The Piano, bewitched by the hole in Holly Hunter’s tights, I place a gossamer touch on the stitching with my finger end, barely perceptible. I do it for the teenage wrist-spinner in me that has lain dormant for two decades. This could be the cure, like drinking from the grail. I do it for the future grandkids. I do it because Warnie wouldn’t mind, would he? He would have admired the chutzpah, surely?

Since returning home from Australia I haven’t yet attempted to bowl a fizzing leg-spinner. I have, however, been racked with guilt. I call Jed Smith and confess. “You scoundrel!” he laughs as he assures me he isn’t going to come after me. “It will firmly be behind security glass in the exhibition,” he adds, pointedly. “Shane Warne’s magic and skill spoke to people on a personal level. I could see how blown away you guys were coming face to face with these objects. It made me even more excited for the exhibition to open.”

I smile, with no little relief and we say goodbye. I rub my thumb across my forefinger. Magic.

.png)

6 hours ago

2

6 hours ago

2