Like so many football fans, I have my own routines and rituals with which I tie together the home games of a league season. Last year, one such routine involved the older gentleman in the seat to my right. I’d nod hello and, above the strains of pre-match music, ask him what he thought of Norwich’s chances – 23 times I asked, and 23 times he replied along the lines of: “We’ll probably get thumped” or “I don’t see where our goals are coming from.” A shred of contempt would be spared for the referee. Always, the referee was known to him and, always, I’d be forewarned that this or that referee was an “arsehole”, a “wanker”, or – once – “an arsehole and a wanker”.

This neighbour of mine was a retired engineer, a Norfolk boy, and a follower of both first team and academy, home and away. He was just one of thousands with a season ticket at the back of Carrow Road’s lower Barclay stand: a Saturday afternoon companion, a stranger at the start of the last season who became a little less strange as the matches went by. I was able to glean, for example, that after decades of loyal (if pessimistic) fandom, he would soon be moving to Yorkshire with his partner, unable to ignore his dreams of the Dales. He had already decided that he wouldn’t be renewing his season ticket. My first year in this part of the ground was his last.

There are other faces I recognise every week, most of whom returned to their usual seats after the long summer break: the dad and his two young lads in front, the Scottish-born council worker to my left, and behind me the woman who, unusually, attends games with the best friend of her grownup son. In my first season among these people there were moments – celebrating a late equaliser, belting out the club song before kick-off – when I felt quite close to them. So begins the process by which tentative exchanges on the terrace can provide the foundations for more meaningful connections … and perhaps even genuine friendships.

From the outside, football fandom looks a lot like a cult. Every other week, we troop down to the stadium in our thousands, wearing the same colours, singing the same songs. We share a sense of collective triumph after a goal – just as we bear, together, the humiliating misery of the net bulging at the other end. It’s not a religious experience but, to me, there’s something liturgical about the timeworn routines, the replica shirts, and the almost spiritual reverence in which the club and its players are held. In such an environment, how could you not make friends with the people around you?

Of course, it starts with the easy stuff, the stuff that’s right there on the pitch. Talking about the last game, about today’s lineup, transfer rumours, the weather. Is our striker Josh Sargent still injured? Who’s that Danish chap we’ve been linked with? In time, real life bleeds into these conversations. After all, in the 40-plus hours you’ll spend together over the course of a season, it’s not too great a leap from grumbling together about Norwich midfielder Kenny McLean’s latest suspension to asking someone what they do for work. By the time you reach the business end of things, you’re sharing chips on the concourse and celebrating goals arm in arm. Next time out, in the expectant quiet before the whistle, you may even take the greatest of leaps and ask your neighbour’s name. Maybe.

In my case, it took until the second half of last season to properly introduce myself to any of the people in my vicinity. “Isn’t it ridiculous that I see you every week, and I don’t even know what you’re called?” So said the man two seats to my left at Christmastime, glowing, perhaps, with the spirit of the season. We swapped names, shook hands, and now I know I’ll get a smile and an “All right, George” before each kick-off.

As a working-class man (and a graduate of the grunt-and-nod school of social interaction), I can recognise that this behaviour is typical of men like me: grumbling for hours about the manager’s tactics but waiting months or years for an actual introduction. But at least football gets us talking. And, given time, the social glue of fandom can easily bind strangers – men and women, working-class or otherwise – into mutual acquaintanceship. From there, deeper connections beckon.

I’m not the first person to bang the drum for the potentially transformative power of football friendships. In October 2023, Norwich City FC released a short video to mark World Mental Health Day. Its resonance was such that, on holiday last year, a Portuguese man recognised the Norwich crest on my cap and told me, unprompted, that he’d seen the video and had cried watching it.

At the start of the clip, we see two men taking up their seats, and then we follow these men from game to game, witnessing the celebrations and commiserations of the stands, interspersed with snatches of conversation (“How’s the week been?”). In a genuinely touching and unexpected ending, we discover that one of the men had been suffering in silence all the while. At the start of the following season, a scarf is laid on his empty seat: an impromptu memorial for one of the 4,200 men who kill themselves in England and Wales each year. Indeed, in a country in which men die by suicide at three times the rate of women, we should look to the still male-dominated football stadium as an arena in which usually taciturn men may be persuaded to open up. In this context, striking up a football friendship may be more than just a pleasant way to fill the half-time interval. Talking to the person next to you could save a life.

It was a coincidence that when that video was released, I had recently finished drafting my debut novel, Season. The story follows two male football fans (unnamed, of course) as they gradually form their own slow-burn intergenerational friendship in the stands of a fictionalised club – albeit one that closely resembles Norwich. As the matches tick by, both men come to lean on one another in unexpected ways, their shared stake in the football becoming a refuge from the world beyond the stadium. From what readers have told me, this plot has its parallels up and down the country. And, for many, the significance of sporting friendships has only grown as the sense of community has diminished almost everywhere else in British civic life.

Certainly, I felt a strange sadness when the whistle blew at the end of the last campaign and my season ticket neighbour said his goodbyes to everyone around him – including some diehards who had had their seats for almost as long as him. He and I never made it to the point of friendship – and even with a few more seasons under our belt, we might never have got there. But, still, it was bittersweet, after all those hours together, to wish him a good summer, knowing I would never see him again.

He was one of those whose names I never caught, but I still found myself thinking of him when I returned to Carrow Road in August. The club may have lost just one of its many longsuffering fans, but I’ve lost part of my pre-match routine. Indeed, nobody has taken up his old season ticket; the seat I always thought of as his is now occupied by a carousel of casual fans, strangers who take his place for one match before giving way to somebody else next time out. This is why, in recent weeks, after a goal or a shocking miss, I’ve looked more readily to my left. There stands my acquaintance from north of the border, who has turned out to be an eager conversationalist, always willing to share from his own surplus of gripes and obsessions.

Yet I know that next time a particularly hopeless referee screws us out of three points, I’ll still end up thinking of my old neighbour and wondering whether up there, in North Yorkshire, he’s finding it any easier to see the positives in life.

Season by George Harrison is published by Eye Books. To support the Guardian, order your copy from guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply.

In the UK and Ireland, Samaritans can be contacted on freephone 116 123, or email [email protected] or [email protected]. In the US, you can call or text the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline on 988, chat on 988lifeline.org, or text HOME to 741741 to connect with a crisis counselor. In Australia, the crisis support service Lifeline is 13 11 14. Other international helplines can be found at befrienders.org

Manchester City

‘It’s a dopamine hit – football, getting to hang out with these guys. I love them to bits’

It started – all the best things do – with a big, messy hug. And then – not so good – a night in A&E. The year was 2009. Manchester City, at home to Hamburg in the Uefa Cup, equalised from the penalty spot. “Ask any City fan about the best atmosphere in the stadium, they’ll talk about that night,” says Andy, who was at the game with his brother Dave.

They knew Dan and Olly, who stand in the same part of the ground (no one sits down in block 110), but their interaction hadn’t gone much beyond nods of acknowledgment. That changed with Elano’s spot-kick conversion, and the grab-anyone-within-reach jubilation that followed. For Dan, though, the ecstasy quickly turned to agony. “I felt this sharp pain in my right eye. We were celebrating, hugging and cheering, the atmosphere was buzzing, but I couldn’t really see. My eye was killing me.”

Dan left the match and went to hospital, with a scratched cornea. He still doesn’t know how it happened; it might have been Olly – his best mate since the age of four – waving his cowbell around. “Olly brought a cowbell to the game, to get the atmosphere going.” But the incident, then Dan turning up to the next game with an eye patch, proved to be the beginning of beautiful friendship. “As catalysts and chain reactions go in terms of friendships, it’s quite unique.”

Dan and Olly started joining Andy and Dave – and then, increasingly, Andy’s son Liam – for a beer at half-time. In fact, Olly bought Liam his first pint. (I won’t say how old he was: “He was very tall, I just assumed,” says Olly, in a lame attempt at justification.) The friendships progressed from beers at half-time to beers on the way to the game, and an invitation to Andy’s 40th (he’s 13 years older than Dan and Olly). Other family members, friends and partners started going to games – Andy’s daughter Phoebe, and Dan’s girlfriend Tara. And Katie, who was with another group in the family stand. “But there wasn’t much atmosphere there,” Katie says, “so I used to sneak out, go to 110, get the drinks round there.” Another reason she was sneaking off to block 110 was Olly, whom she’d met clubbing and was dating. They were married in 2014, with the City gang very much in attendance. There’s a photo of them all at the wedding.

I’ve got some of them on a Zoom call: Dan, Andy and Liam (22 now and legally allowed a pint), Katie and Olly. Katie and Olly’s boys – Maddox, nine, and Phoenix, six – are clambering around, in and out of the call. They’ve started going to games, too, where they clamber around the Etihad Stadium.

The group’s friendship has transcended football. Everyone went to Olly and Dan’s 40ths when they, too, hit the milestone. They go clubbing and to gigs together; they’ve seen each other’s kids grow up. Dan and Tara went on holiday to Ibiza with Andy and his wife, Emma. “That’s a true test of friendship, when you spend more than 24 hours with them,” Dan says. A test they seem to have passed: Dan now also uses a desk in Andy’s office.

Covid was difficult, but on match days they met up on Zoom, to watch (and drink) along together. “It wasn’t the same – I missed the day out,” says Andy, who is now 53. “These guys make me feel young. I’m still a 40-year-old when I’m with them. They’ve also been fantastic role models to my son.”

Liam, who graduated from university earlier this year, agrees. “Coming to City and seeing these guys, that’s what gets me through the week.”

“It’s a dopamine hit,” says Dan. “It’s helped my mental health massively – football, getting to hang out with these guys and call them my friends. I love them to bits.”

“They’re a sound bunch,” says Olly. “We could be winning, we could be losing – it doesn’t really matter as long as we’re together.”

I’m on the verge of welling up now. City did win that match against Hamburg in 2009, but lost on aggregate over the two legs, and went out of the competition. But, apparently, they have had some success since …

Arsenal Women

‘Meeting each other was like finding gold’

Bonnie’s confidence was low in 2022. It had taken a hit during Covid, and on top of everything she’d been made redundant. “I was finding it hard going out, being too far from home,” she says.

At the same time, the England women’s team won the Euros and Bonnie found herself getting into women’s football. On a freezing Sunday evening, she plucked up the courage to take herself to an Arsenal game at Borehamwood in Hertfordshire (the women’s team weren’t playing a lot at the Emirates then). Walking from the station to the stadium, she felt quite alone, but things got better inside. “I saw Stina Blackstenius and Beth Mead in the flesh – people I’d seen on TV – and I got all fangirl.”

Bonnie only made it to half-time, due to a combination of nerves, the cold, and “I think it was Beth Mead who kicked the ball so hard it hit the back of the area I was sitting in and then hit my shoe – I was so embarrassed!” But she loved the atmosphere. “I thought, I’ve got this far, I’m going to give myself a push.” On a supporters’ club forum, she found out about a pub people went to before games and decided she’d do that next time …

Jemma had a different path to the Pick & Shovel in Borehamwood. She enjoyed football as a kid, but isn’t from a football family. When she got older, she was told that girls didn’t play football. “And that was kind of the end of that, until uni, where one of my housemates, who was Spanish, was obsessed and we watched the Euros together.”

Jemma managed to persuade some friends to go with her to watch Arsenal, but they only wanted to go once, for the experience. Jemma was hooked, though. She had heard about the Pick & Shovel, so for the next game, she went along alone, nervously. “I walked round by myself for an hour. I walked in, then back out. Then a friend texted asking if I’d got to the game, so I was like, I’m going to have to do this.”

Inside, she found people in Arsenal shirts, standing around chatting. “No one seemed to know each other very well, just people saying hi.” One of them was Bonnie: “And I thought, she seems fun, I’ll cling to her.”

They clung to each other, and started going to games together. Then in 2024, two became three when they met Hollie at the League Cup final at Wolverhampton’s Molineux Stadium (where Arsenal beat Chelsea). Sometimes, being in a group gives you the courage to get more involved and be more vocal. And, among this trio, Hollie’s the most vocal. “I’m really invested in what’s happening on the pitch, and if I don’t agree with something I will call out the people who’ve done it – not very politely most of the time. We often tell the ref they need to get their eyes checked, but not in such friendly terms,” she says.

Hollie says all three women are completely different. “But somehow it works really well, and I don’t understand how it does, but I’m so grateful.”

Bonnie agrees: “But our morals align, and obviously our support for Arsenal. It was like finding gold.” They’re now best mates, and they text and chat between games. When Arsenal reached the final of the Champions League in May, the trio went to Lisbon together and shared an Airbnb. On the day, Mead teed up Blackstenius to stun favourites Barcelona and take the title. “For me, it was one of the best days of my life,” Bonnie says. “And the celebration afterwards, we filled a whole street, everyone standing on chairs singing, sharing the same energy. You get the feeling that you belong somewhere.”

Merthyr Town

‘We give each other endless amounts of abuse, but we’ve also got each other’s back’

Mark and Nigel remember the first time they met, in the early 80s. Not actually on the terraces, but heading to an away game: Merthyr Town were playing Cardiff City in the Welsh Cup. “Me and my then girlfriend were having a nice kissing session on the train, while Nigel was getting hassled by some Cardiff fans,” Mark says.

Nigel remembers Mark, who was a skinhead at the time, disentangling from his amorous liaison and emerging from under a sheepskin coat “like David Jason’s in Only Fools and Horses” to come to his aid, and has been grateful ever since. Merthyr lost the game 5-0, but Mark and Nigel both gained a mate for life, and they’ve watched the Martyrs together from the same spot at Penydarren Park ever since.

And it’s not just the two of them. Mike showed up, later in the 80s. “He’s from a different part of town, a different religion – we’ve still got Catholic and Protestant schools in Merthyr,” Mark says. The group grew, and started a fanzine: they became the Dial M for Merthyr lads.

There’s now a core of 15 or 20 pals, and I’m on a video call with five of them: Mark, Nigel and Mike, plus more recent recruits Louis and Jason, speaking from in and around Merthyr Tydfil. “An oasis of football in the sea of rugby in the south Wales valleys,” says Mark. “Since the deindustrialisation of our area, the only thing we have left is football.” Actually, Mark’s not at home right now. He’s gone to another away game – Wales’s World Cup qualifier against Kazakhstan; he’s in a hotel room in the capital, Astana.

Oh, and they’re all part-owners of the club, which became fan owned in 2010 after liquidation. Mark, Nigel and Mike were instrumental in that, too, but this is more about terrace friendship than business affairs.

For home games at Penydarren Park, the Dial M lads stand in the CTM memorial stand – not its official name, but what they started to call it after one of their lot, 72-year-old Colin the Monk (named after a bad haircut), didn’t show up for a few weeks. “We thought he was dead, so we put up a little plaque,” says Mark, who does most of the talking. “But, a few weeks later, he reappeared. He’d just moved away with a new girlfriend.” Colin the Monk is off again soon, to live in the Philippines.

They look out for one another, even if they don’t see much of each other away from the CTM stand. “It’s a bit like the Cheers bar, where everyone knows your name,” says Mark. “You can be having a really bad week, you could be depressed, we’ve had a few of those: three o’clock and so-and-so’s not here, let’s give him a ring and see what’s up.”

Mike tells me about the time he was experiencing depression and anxiety, and how the Dial M lads were there for him. “It’s a safe place – we know where we are. I know we give each other endless amounts of abuse, but there’s a line, and we’ve also got each other’s back. You can tell anybody anything, really, if you’re not right. We did have a friend who took his own life – he wasn’t in our group, but he was a Merthyr fan and it hit us all hard.”

Mike says they’ll be there for each other even after they’ve gone. “Some of these boys, they’ll be carrying my box. I’ll be carrying some of theirs.”

An “extended family” is how Jason describes it. He brings his actual family – his three kids, including his five-year-old daughter. The first Dial M wedding came after Mark took his sister to a few games. “She fancied one of our mates, Mick, and they ended up getting married.” And Mark’s six-year-old grandson is going to his first game, against Worksop Town (Merthyr play in the National League North), the Saturday after we talk. Mark’s dad, who’s been going since 1949, will be there, too; there’ll be four generations of the family in attendance.

Nigel is the joker in the pack. Halfway through the call, he nips off and reappears wearing a wig. He says he found it lying around the hospital where he works, “saving lives” (as a porter). They’re not a clique, he insists. “Whoever wants to come and join us, you’re welcome, but you’ve got to take the banter. If I say you’ve got a big nose you’ve got to take it, know what I mean?”

Oh, and Louis does the songs, mostly Abba ones, with new lyrics. Go on, Louis, give us a blast, I say. So he does, choosing the one they sing for centre-forward Ricardo Rees, to the tune of Voulez-Vous:

Ricardo (aha)

Running down the wing (aha)

He’s scoring all the goals (aha) …

An hour with the Dial M for Merthyr boys in the valleys of south Wales (and the Kazakh Steppe) has been a blast, and given me a little taste of what they’ve been up to together for more than 40 years: taking the piss and looking out for each other.

Wigan Athletic

‘Back then, not many women went to matches. I saw Julie and thought: not bad’

Wigan were playing away – to Stockport, Julie thinks, but isn’t 100% sure; it was a while back – in 1982. She was getting a lift with her friend Terence, as she often did. “He took people to away games and I used to just get in with anyone else who was going.”

On that day, Dave was going. “He’d taken someone’s place, just happened to be there.” First impressions? “Yeah, I thought, he’s a bit of all right,” she laughs. “And that was it!”

What about Dave, does he remember what he was thinking? “Not bad,” he says, deadpan. I don’t think Dave is prone to overexuberance. Actually, he was surprised more than anything. “Back then, not many women went to football matches.”

In those days, some grounds didn’t even have women’s toilets. Julie remembers one away game – in Middlesbrough, possibly – when Dave “had to go into the toilets and wait for the men to come out and then I could go in. He kept them out until I’d been.”

He did that because, guess what, they got together at the last game of that season, in May 1982. “They ran a train – a football special, they used to call them – to Aldershot for the game,” says Julie. “We both went, along with Terence and some others, and that’s kind of when we decided we wanted to be together.”

Which they have been since, though it took them until 1988 to get married. “I was thinking about it, considering my options,” says Dave, typically. “When I met her I had a full head of hair and a full bank account, now I’ve not got either,” he moans.

They’re speaking from their home in Wigan, sitting on the sofa, Julie doing most of the talking, Dave occasionally chipping in sardonically. Wigan Athletic has been a big part of their life together. They used to go to both home and away fixtures, hardly missing a game.

Julie’s the louder of the two on the terraces. “I like going to away games, singing and chanting behind the goal. I enjoy that, more than him, probably. I like the atmosphere.”

Is Julie more of an ultra then? “She can be,” says Dave. She tells me about an altercation with a couple of Millwall fans. “They wanted to fight me, and I had two young children with me!”

Their kids – Hannah and Amy – got wrapped up in warm clothes and lugged along to home games as babies. In fact, Amy was for a time the youngest member of the Wigan Junior Latics, after Dave signed her up for the team when she was just 30 minutes old. “Dave called his mum first, said, ‘She’s here’, then got her registered,” says Julie. And Hannah became a footballer; she has played for several sides including Blackburn Rovers Women.

Julie and Dave have seen highs and lows at Wigan. The arrival of three Spanish players in the 90s – the three amigos (including Roberto Martínez, who would later become manager) – was a high. Then the Premier League, winning the FA Cup in 2013, playing in Europe and an away trip to Bruges. It beats Stockport or Middlesbrough, even if it was raining, there was no beer in the stadium and the score was 0-0. “The atmosphere going over on the ferry, then all the Latics fans and flags in the square in the centre of Bruges – it was fabulous,” says Julie.

The club going into administration in 2020 was definitely a low. “I wouldn’t wish that on any football fan,” says Julie. Now Wigan are in the third tier, League One. Julie and Dave still go to all home games together, but have to take it in turn for away matches – not because of the girls (who are now grown up), but because of Dora their cockapoo.

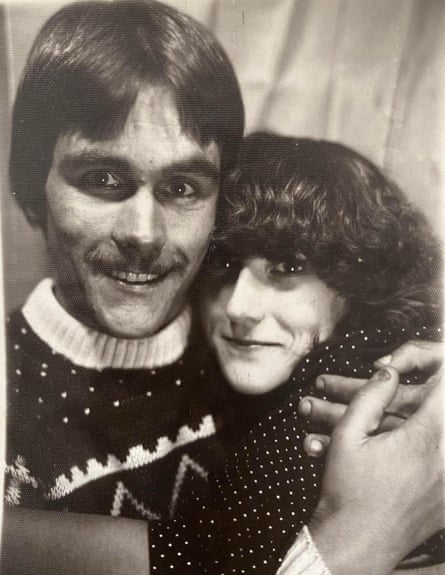

After speaking to them, I get an email from Julie with a few attachments. There’s video of the scenes inside Wembley at the final whistle after Wigan beat Man City in the 2013 FA Cup final. There are some photos, too: one of her and Dave soon after they met; a picture of Julie, the girls, and the Three Amigos; and one from last Saturday of their elder daughter Hannah who has just scored on her debut for her new club, Wigan Athletic.

St Johnstone

‘You can go months without seeing pals, but Saints are a constant’

Emma used to go to McDiarmid Park, home of St Johnstone in Perth, with her dad. At half-time during one game, probably around 2008, she found herself next to Cary and Pam in the queue for the toilet. They recognised each other from school in the late 90s, even though they weren’t in the same year.

They reconnected, bonded again, and had a big night out on the town when Saints were promoted to what was then the Scottish Premier League in 2009. And they changed their season tickets so they could sit together, in the east stand. When Emma’s dad died in 2016, having Cary and Pam’s support was a huge comfort. “I valued that they knew him. They came to the funeral, and they were there when his name was announced in a list of supporters who had passed away that season. As time has gone on, people in my life have increasingly not met him, so that means a lot.”

I’ve temporarily been allowed into their WhatsApp group, Oh When the Saints, on a group call. Clare is the fourth and most recent member. Pam met her at a hen do, and they got chatting about football. Then Clare started going to away games with them. At home, she sits in the main stand. It’s posher, the others say. “More leg room,” she says, apologetically. There is one more member of the gang – Frazer, but, well … he’s a bloke. He’s useful, though – he has a car, and he doesn’t drink. Apart from Emma, who now lives in Edinburgh, the group are all still in Perth.

Cary went to her first game as a kid with another friend and was hooked. “I think that friend slowly lost interest over the years and when I discovered Pam was a Saints fan I just migrated over and joined her family.”

Pam first went to a match when she got a free ticket at primary school. “My sister is a fan, too, and with my mum it was a case of, if you can’t beat them, join them, so she got a season ticket.” For Pam, going to games brings structure, and regularity, to friendships. “You can go weeks and months without seeing pals as everyone has a busy life, but Saints are a constant and allow us to catch up regularly.”

More women and families attend St Johnstone games now than when the gang started going – including a group of slightly older women who sit near them – but, beyond that, the stands are still mostly a sea of men, some of whom they have nicknames for. “The Dutchman”, for example, who’s not actually from the Netherlands but is so called because he once yelled at the ref: “If that was a foul, you’re not bald and I’m a fucking Dutchman.”

The four friends are as shouty, and as sweary, as anyone else there. They join in on all the songs. Except one, which gets sung when St Johnstone play big rivals Dundee. I won’t include the lyrics here, but there is a line about domestic violence. “I cringe every time I hear it,” says Pam. “You’ve got your wife and your children sitting beside you – what kind of example is that to a young girl?”

“Or young boy,” adds Cary. Anyway, Pam put her head above the parapet. Racist and sectarian abuse at games gets called out, and she wanted to do the same in this case. So she did, on a Facebook banter page. “I got a lot of support, but also a lot of people jumped in and said I was a snowflake, go back to the kitchen, that kind of rhetoric. But I’m glad I did it.”

Clare, who was at the most recent away game at Dundee, chips in. “Somebody started it, but it died out pretty quickly. So I think the message is getting over.”

And there’s another sign of progress for St Johnstone’s female supporters: the women’s toilets in McDiarmid Park now have bins for sanitary products, which wasn’t the case when Emma, Pam and Cary reunited there all those years ago.

Birmingham City

‘We used to sneak under the turnstiles. I think I was the only south Asian around at that time but being young, I was none the wiser’

Caroline and Micky both have blue blood. Not in a royal way, in a Birmingham City way. Micky’s family lived on St Andrew’s Road; he could see the stadium from his school. “We used to sneak under the turnstiles. I think I was the only south Asian around at that time but being young, I was none the wiser.”

Later, when he was in his teens, Micky used to go early and hang around to get autographs of the players. That’s when he met a fan called Bill. Bill was older, in his 20s; he knew some of the players and stewards. “We became friendly, had the same passion for the club.”

Micky wanted to join Birmingham’s official supporters club, to go to away games. “I was blocked. I realise now it was probably because they didn’t want any dark faces or whatever.” This would have been the late 60s; Micky is now 70.

“That really niggled me. I thought: nobody’s going to deny me going to see my club.” He challenged it, and went to the paper, the Sports Argus. Some of the stewards helped; Bill, of course, was on his side. And eventually, when he was 18, Micky got his membership and could go to home and away games with Bill.

Caroline was three in 1971 when Bill, her dad, first started taking her to St Andrew’s. “If Blues scored, he would throw me up in the air, so I always wanted them to score. If we won, he’d just be so happy and we’d go to the shop on the way home and he’d get treats.”

Caroline remembers seeing Trevor Francis, Birmingham’s great striker and Britain’s first £1m signing, play. And meeting Micky. “My dad said, ‘There’s Mick’, and there was Mick.” Bill died eight years ago. “My dad would’ve been in his 80s now, and it’s not great to say, but some people of that generation … you know. But my dad brought us up to treat everyone equally. I knew why Mick was my dad’s friend; he would have been that person to say to Mick, ‘Come with us, we’ll get you in.’ That’s who he was, and I’m really proud of him for that.”

So Caroline grew up watching the Blues with her dad and Micky, then later with Micky’s son Bik, too. “We went to Bik’s wedding – that was lovely.” Caroline’s daughter Molly went to a few games, but when Bill died she started to go regularly, sitting in his seat. “I said, ‘Do you want me to sit there – because it’s on the end it’s a bit cold,’” Caroline tells me. “And she’s like: ‘No, I want to sit in grandad’s seat.’”

Micky, Caroline and Molly sit together in the Main Stand; Bik’s a few rows away. It means the world to Caroline having Micky there. “He brings back memories of my dad. He doesn’t have to say anything. Something might happen in the game that’s emotional, he’ll give me a look, and I know he’s thinking about my dad.” Micky says he still dreams about Bill and that Caroline – and Molly – “are part of my family. I love them to bits.”

In 2016, Micky and Bik set up the supporters group Blues 4 All with the aim of getting more people who look like them into the crowd. “It’s got better and better,” says Micky. “We never used to see Asian girls and women. Now, because of winning the Euros, Asian women are bringing our daughters to our academy, which is fantastic.” They haven’t had an Asian player break through in the men’s side yet. “But we’ve got the first Punjabi girl, Riya Mannu, to sign for Birmingham City – she scored on her debut.”

It seems a long time ago that Micky wasn’t allowed to join the supporters club. “We’re moving in the right direction. Football brings families and everybody together,” he says.

Oh, and there’s a new member in their family group. Molly has started bringing her two-year-old son Jude – Caroline’s grandson, Bill’s great-grandson – to games. The blue bloodline goes on.

.png)

2 months ago

31

2 months ago

31