Orla Guerin

Senior international correspondent

Reuters

Reuters

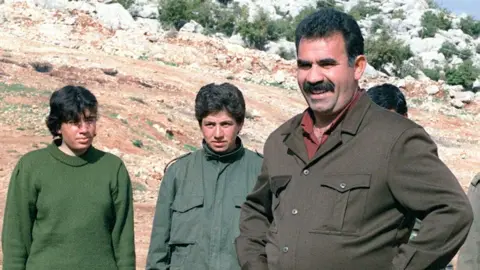

Abdullah Ocalan, the leader of the PKK, called on the group to disarm in February.

After 40 years, with 40,000 people killed, and without securing a Kurdish homeland, the banned Kurdistan Workers Party, the PKK, is ending its war against the Turkish state.

This signals the end of one of the longest conflicts in the world - a historic moment for Turkey, its Kurdish minority, and neighbouring countries into which the conflict has spilled over.

A spokesman for President Recep Tayyip Erdogan's ruling party said it was an important step towards a country free of terror.

But what will the PKK get for disarming and disbanding? So far the government has made no promises – publicly at least.

Sheltering inside a tea shop from a sudden violent hail storm that battered the ancient city of Diyabakir, Necmettin Bilmez, 65, a driver, was sceptical about what might follow.

"They [the government] have been tricking us for thousands of years," he said.

"When I get an ID card in my pocket saying I am Kurdish, I will believe everything will be solved. Otherwise, I don't believe in this."

Sitting nearby on a small woven stool, Mehmet, Ek, 80, had a different view.

"This has come late," he said.

"I wish it had happened ten years ago. But still anyone from any side who will stop this bloodshed, I salute them," he said, tipping the top of his flat cap.

"This conflict is brother on brother. The one who dies in the mountains [PKK] is ours and the soldier [from the government] is ours.

"We are all losing, Turks and Kurds."

He wants an amnesty for PKK fighters – like many here - and the release of jailed Kurdish politicians.

"If all that happens it will be a beautiful peace," he said.

In this majority Kurdish city in south-eastern Turkey - the de facto Kurdish capital - we found a muted response to PKK's announcement.

The city has been scarred and reshaped by the conflict.

Turkish forces and the PKK battled in the heart of Diyarbakir in 2015. You can still see the rubble of buildings flattened by the Turkish army.

Many local people told us they welcomed peace, or the idea of it, and wanted no more deaths - Turkish or Kurdish.

"No one has achieved anything," said Ibrahim Nazlican, 63, drinking tea in the shade of the towering city walls, which have guarded Diyarbakir since Roman times.

"There is nothing but harm and loss, on this side and on that side. There are no winners."

The conflict has ranged from the mountains of northern Iraq – which became PKK headquarters in recent years - to Turkey's biggest cities.

Outside an Istanbul football stadium in 2016, a PKK affiliate carried out a double bombing killing 38 police officers and 8 civilians. Many Kurds and Turks are hoping this is the end of a dark chapter, which has claimed 40,000 lives

Getty Images

Getty Images

Some have called for the release of PKK founder Abdullah Ocalan who is currently imprisoned on an island off of Istanbul.

The PKK decision lay down its arms followed a call in February by its jailed leader, Abdullah Ocalan, who said there was "no alternative to democracy".

For now, the 76-year-old remains in his cell in an island prison off of Istanbul, where he has been held since 1999.

To his supporters, he remains a heroic figure who has put their cause on a global agenda. They want him released.

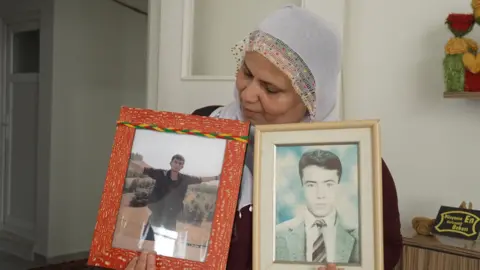

Menice, 47, is among them. She insisted his release was the key to a new dawn for the Kurds, who account for up to 20% of the Turkish population.

"We want peace, but if our leader is not free, we will never be free," she said.

"If he is free, we will all be free and the Kurdish problem will be solved."

BBC/Ozgur Arslan

BBC/Ozgur Arslan

Menice lost her eldest son during a Turkish airstrike after he joined the PKK.

She is surrounded by family photos of loved ones who have died fighting for the PKK - which is classed as a terrorist organisation by Turkey, the UK, the US and the EU.

She has lost five relatives including her brother and her oldest son Zindan.

He joined the PKK at 17, and was dead at 25, killed in a Turkish airstrike three years ago.

Menice's eyes fill with tears as she tells us how he used to help her with the housework.

His path may have been mapped out from birth.

"We named him Zindan [meaning cell] because his father was in prison when he was born," she told us.

One large photograph hangs on the wall shows Zindan alongside his brother, Berxwendan, who followed his footsteps "up the mountain" to the PKK, when he reached the age of 17.

Berxwenden is now 23. His mother did not know if he was alive or dead until he sent his family a photo of himself during Ramadan in March.

Menice is hoping her surviving son may now come back.

"I hope Berxwendan and his friends will come home. As a mother, I want peace. Let there be no killings. Hasn't there been enough suffering for everyone?"

But does she believe that there can be peace between Turkey and the Kurds?

"I believe in us, in Ocalan, and our nation [the Kurds]," she said firmly.

"The enemy [the Turkish authorities] has forced us not to believe in them."

However, pro-Kurdish political parties have some leverage.

Erdogan needs their support to enable him to run for a third term as president in elections due in 2028.

For its part, the PKK has been hit hard by the Turkish military in recent years with leaders and fighters hunted down in drone warfare.

And regional change, in Iran and Syria, means the militant group and its affiliates have less freedom to operate.

Both sides have their reasons for doing a deal now. That may be grounds for hope.

.png)

4 hours ago

2

4 hours ago

2