Getty Images

Getty Images

A hostile immigration environment is prompting some Indians in the US to think of returning home

US President Donald Trump's abrupt decision to hike H-1B visa fees to $100,000 has prompted policymakers in Delhi to woo skilled Indians back home.

A bureaucrat, who works closely with Prime Minister Narendra Modi, recently said that the government was actively encouraging overseas Indians to return and contribute to nation-building. Yet, another member of the PM's economic advisory council told a media conclave that H-1B visas have always served the interests of the host nation, and so the hike in fee boded well for India's ability to attract global talent.

The crux of these arguments is that the time is ripe for India to engineer a reverse brain drain and lure some of the world's most talented professionals in technology, medicine and other innovative industries, who'd left the country in the past 30 years, back to the homeland.

There is some anecdotal evidence to suggest that an increasingly hostile immigration environment in the US is prompting a few Indians to think along these lines. But getting hundreds of thousands of people to ditch Bellevue for Bengaluru will be easier said than done, several experts told the BBC.

Nithin Hassan

Nithin Hassan

Nithin Hassan (left) gave up a $1m job at Meta in the US to return to India

Nithin Hassan is among the few Indians who had settled in the US for the last 20 years but took a leap of faith and decided to move back to Bengaluru - often called India's Silicon Valley - last year.

It wasn't an easy call. He quit a million-dollar job at Meta to plunge into the uncertain world of start-ups.

"I've always wanted to start something of my own, but my immigration status in the US limited that freedom," Mr Hassan told the BBC.

Since his return, Mr Hassan has launched two start-ups, including a platform called B2I (Back to India) that helps other Indians settled in the US "navigate the emotional, financial and professional challenges of returning home".

He told the BBC that the US's immigration policy shifts in recent months had led to a sharp spike in enquiries from people looking to relocate, and the H-1B fracas could accelerate this trend.

"Many professionals now accept that a green card may never come, and queries to B2I have surged - nearly tripling since Trump's second term began. In just the last six months, more than 200 NRIs [non-resident Indians] have reached out to explore return options," said Mr Hassan.

Other headhunters who scout for Indian talent from US universities corroborate this change in sentiment.

"The number of Indian students from Ivy League universities looking to come back to India after their studies has risen by 30% this season," Shivani Desai, CEO of BDO Executive Search, told the BBC.

She added that the uncertainty is also making senior Indian executives "think harder about their long-term careers in the US".

"While many are still anchored there, we see a noticeable uptick in CXO and senior tech leaders exploring India as a serious option," Ms Desai said.

Such change in attitudes could also be aided by a massive boom in Global Capability Centres (GCCs) - or remote offices of multinational companies in India in recent years - that have thrown up viable work opportunities for returning Indians.

These offshore operations could be where those from the tech industry relocate to if the US closes its doors to them, making GCCs "increasingly attractive to talent, especially as onsite opportunities decline", according to asset management firm Franklin Templeton.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Countries such as Germany have welcomed skilled Indians after Trump hiked H-1B visa fees

But driving reverse migration at scale will require a concerted and serious effort by the government, and that's currently missing, says Sanjaya Baru, former media adviser to Prime Minister Manmohan Singh and author of Secession of the Successful: The Flight out of New India - a book on India's brain drain.

"The government will have to go out and actually identify individuals - including top-of-the-line scientists, professionals and entrepreneurs - it wants back. That requires effort, and it needs to come straight from the top," Mr Baru told the BBC.

He said this was what Jawaharlal Nehru, India's first prime minister, did back in the day to get top minds in areas like space and nuclear technology back home and build institutions like the premier Indian Institute of Science.

"They were driven by a strong sense of purpose and nationalism. Where is the incentive to come back now?" said Mr Baru.

On the contrary, there are both pull and push factors that have led to highly qualified professionals consistently leaving the country, Mr Baru said, and India has celebrated this trend, rather than arresting it.

The pull factors include a growing number of countries offering golden visas and citizenship or residency by immigration programmes.

In fact, even as the US tightened its H-1B visa regime, countries such as Germany immediately laid out the red carpet for Indian skilled migrants, with its ambassador pushing the country's credentials as a "predictable and rewarding destination".

Getty Images

Getty Images

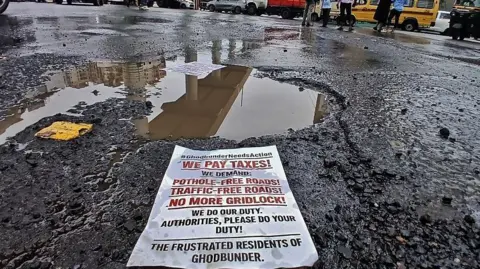

Poor physical infrastructure and urban congestion are major problems in Indian cities

The push factors, meanwhile, are long-standing bugbears - such as a poor regulatory environment, tiresome bureaucracy and a poor ease-of-business climate that has led to an exodus of wealthy, high-earning Indians over the years.

The government's own data shows that over half a million Indians have renounced their citizenship since 2020. Separately, India is among the top five countries globally seeing a flight of millionaires, who are taking up citizenship or residency elsewhere.

Mr Hassan says the government needs to work towards reducing "several friction points simultaneously" if it is really serious about getting overseas Indians to return.

This includes simpler tax laws, targeted incentives such as special start-up visas and fixing other more fundamental problems such as poor physical infrastructure and urban congestion.

It will also mean creating a better ecosystem for the highly educated to thrive - "including elevating the scale of R&D [research and development] and education back home", says Mr Baru - precisely the stuff that made the US such a big draw for Indian talent over the past half a century.

Follow BBC News India on Instagram, YouTube, X and Facebook.

.png)

1 month ago

24

1 month ago

24