Image source, Getty Images

Image source, Getty Images

Bradley Wiggins won the Olympic time trial days after victory at the Tour de France

Matt Warwick

BBC Sport Senior Journalist

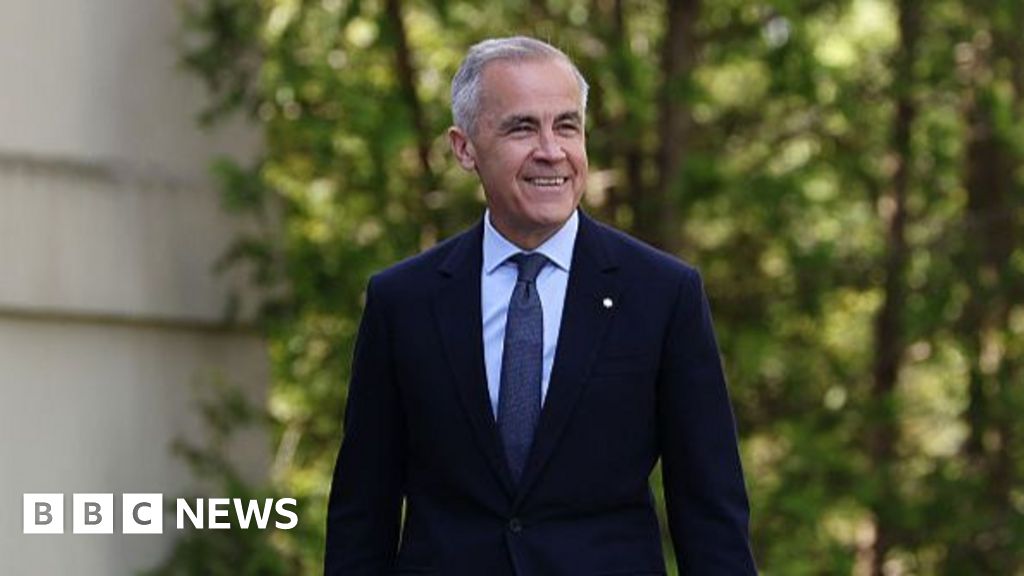

The view from the ornate throne on which Bradley Wiggins sat in the blazing London summer sun in 2012 must have been glorious.

To say all the planets had aligned for him would have been an understatement.

He had become the first Briton to win the Tour de France. He had followed it with an Olympic time trial gold in his home city.

It felt like the coronation of a king. Wiggins, then 32, glided to London 2012 glory under a constantly moving tifo of union flags and Olympic rings.

By 2016, thanks largely to his many successes on the track, he would become Britain's most decorated Olympian thanks largely to many track successes.

With sideburns and the sharpest mod feather cut, he even looked good in Lycra. And by the end of the year, he was endorsing his signature style on top clothing brands and choosing records with his icon Paul Weller on BBC 6 Music.

It seemed as if he had it all.

But then, when his career ended, came the cocaine addiction.

Image source, Getty Images

Image source, Getty Images

Wiggins powers to victory in the time trial during the London 2012 Olympics

Drugs, divorce and bankruptcy: How did it come to this?

In an interview with the Observer, Wiggins said of his post-career cocaine addiction: "There were times my son thought I was going to be found dead in the morning.

"I was a functioning addict. People wouldn't realise - I was high most of the time for many years."

Wiggins - a gangly north Londoner, from a broken home, brought up in poverty - made it to the very top of a sport that requires clinical preparation and a calm head under pressure.

In interviews during his career, Wiggins exuded calm and charm. He seemed to have everything under control.

And perhaps it was, with the hyper-organised, big-budget Team Sky around him between 2010 and 2015, run by Dave Brailsford and Rod Ellingworth - with whom he would win the 2012 Tour, the 2014 world time trial championship and much more.

Wiggins' talent and presence inspired the team to a period of domination in road cycling never before seen.

But post-career, his troubles spiralled.

In 2020, his marriage to Cath came to an end. They have two children: Ben - now a rider himself with Hamens Berman Jayco - and Isabella.

Then came the collapse of Team Wiggins, which he had founded in 2015. The team lacked enough blue chip sponsors, despite having so many talented British riders. There was an awful more of Wiggins' own money invested in the team than most realised.

That, and a cocaine addiction, would spell trouble for anybody's wallet - even a sporting icon. And Wiggins was declared bankrupt.

"I already had a lot of self-hatred," said Wiggins of his post-career addiction. "But I was amplifying it. It was a form of self-harm and self-sabotage. It was not the person I wanted to be. I realised I was hurting a lot of people around me.

"There's no middle ground for me. I can't just have a glass of wine - if I have a glass of wine, then I'm buying drugs. My proclivity to addiction was easing the pain that I lived with."

Mark Cavendish, another retired cycling great, told BBC Sport recently that he had shared many good times with Wiggins.

"He's like a brother to me," Cavendish said. "He has an incredible personality, he's a brilliant friend, and to see his rise and for him to be part of my rise is something we can share forever - and he's someone who's very close to me."

Image source, Getty Images

Image source, Getty Images

Wiggins became a celebrity beyond cycling

The 'Jiffy bag' question

As Wiggins emerged as top-level cyclist, he became the focal point for what those following the sport hoped would be a new cleaner era. The scandal surrounding EPO, and Armstrong, was playing towards its conclusion.

First there was a hard-fought fourth place at the 2009 Tour de France, just behind a fading Armstrong. Then the clean rider and ultra-clean Team Sky were soon at the top of the sport, winning seven Tours between 2010 and 2019.

But, like, Armstrong before him, the questions came flooding in once the pedals had stopped turning.

What was in a 'Jiffy bag' sent to him via Team Sky doctor at a race in 2011?

Two investigations - by the UK Anti-Doping Agency (Ukad) and the Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) select committee - failed to prove what was in the package.

However, the report by MPs on the DCMS committee said Wiggins and Team Sky "crossed an ethical line" by using drugs allowed under anti-doping rules to enhance performance, instead of for medical reasons.

"I would love to know one way or another what actually happened," Wiggins told Cycling Weekly., external

"The amount of times I then got asked 'what was in the package?' But I had absolutely no idea."

The episode left a bitter taste for many. Fans and politicians came to understand how grey an area sports medicine can be.

Cycling's great escape

Pretty much the only thing professional cyclists agree upon is that time on the bike is time alone, away from it all, and a form of crucial therapy.

For Wiggins, it mattered more than most, right from the start. The football fan from a crowded inner-London suburb known needed an escape during his youth.

When his mother pointed him towards the TV to watch Chris Boardman take a very rare Olympic track cycling gold medal for Britain at Barcelona in 1992, he was hooked.

Even if his estranged Australian father Gary had himself been a professional cyclist, this was Wiggins' journey.

But it was a journey soured. Not only by Wiggins' father insisting he would be "never as good as your old man" after an ill-fated reunion during his teenage years; but also by Wiggins' admission that, during his early career, he was "groomed" sexually by a coach.

Image source, Getty Images

Image source, Getty Images

Wiggins with his cyclist son Ben

Back on the bike

Wiggins himself has asked whether there should be more support given to cyclists during and after their careers.

A comparatively open sport, growing ever more globalised by TV money and new structure proposals, road cycling expects athletes to rinse themselves physically day after day, going "full gas" for six hours – something which many feel has to have an psychological and emotional impact.

And he's not alone. British Cycling chief executive Jon Dutton has reached out to Wiggins, and the pair have discussed a number of things, according to sources.

Wiggins was inducted into British Cycling's hall of fame last year, and the new leadership want to pay their respect to a past that yielded many Olympic gold medals and gave rise to an era on the road which changed the face of the sport forever.

For Wiggins, change is coming – but one of his sources of help has raised eyebrows. The disgraced once seven-time Tour de France champion Armstrong makes a habit of reaching out to the fallen,, external and is said to have offered to pay for Wiggins' latest round of rehabilitation., external

Armstrong has established his own media presence on the fringes of the sport he once had total control over. But he is a long way from being forgiven.

Wiggins himself can rebuild bridges, and says he recently rediscovered his sense of peace from riding his bike alone.

He may never return to the victor's throne, but being back in the saddle could be comfort enough.

.png)

2 hours ago

2

2 hours ago

2